Bank of America: In Defence of Structural Hedging

Paul Newson

20 years: Market Risk

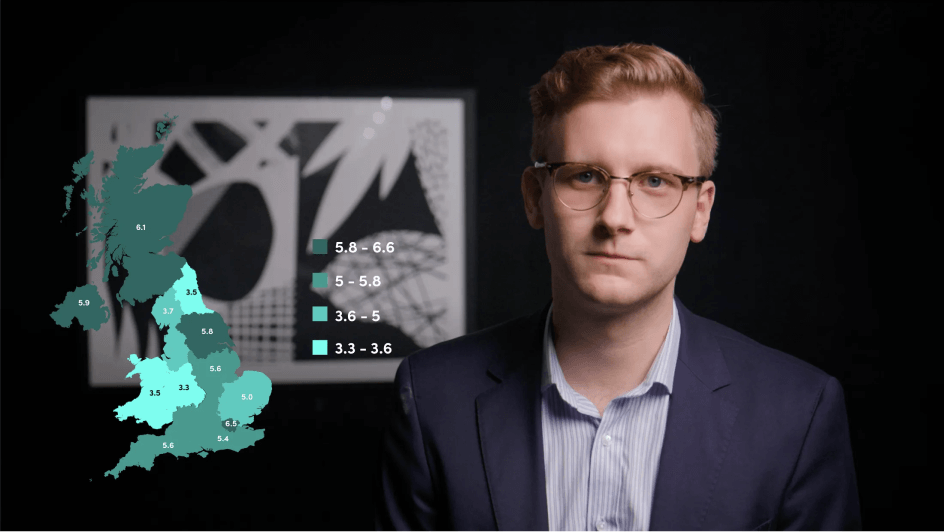

Bank of America (BOA) has recently been subject to a fair degree of criticism because it now appears to be earning less on its deposits than some rival banks. The nub of the argument is that BOA, particularly during the pandemic, continued to invest its deposits at relatively long tenors (up to 10 years) thus locking in – on average – a return of only about 2.4% on something like a quarter of its assets. In contrast, those competitors who more “wisely” invested at shorter tenors are now reaping the benefit of being able to re-invest their assets at closer to 5%. This is being described as an “opportunity missed” thus implying that BOA failed to manage its balance sheet prudently.

Such criticism seems to demonstrate a fundamental misunderstanding of Interest Rate Risk in the Banking Book (IRRBB). Of even more concern, it also implies that banks should, in managing their banking books, adopt a “trading-for-profit” approach. It would seem opportune, therefore, to revisit the topic that is commonly termed the strategic hedging of non-maturing deposits (NMDs) from the perspective that interest rate risk should, wherever possible, be minimised and certainly not explicitly sought.

The first point to make clear is that investing in NMDs at any term longer than overnight is only appropriate if the bank is certain, to a very high degree of confidence, that the deposits will stay with it for at least the length of any selected investment period – i.e. they will not be withdrawn in response to external rate changes, need to be re-priced, or lost for some other reason.

The collapse of Silicon Valley Bank demonstrated the folly of investing in what proved to be very unstable NMDs at a long duration. However, that unhappy incident does not mean that banks whose NMDs are stable should now be managed on the assumption that all depositors will suddenly withdraw their money. That would lead to massive earnings volatility and possibly even bank failures should interest rates fall again. The remainder of this article focuses on banks whose NMDs – or, at least a sizable portion of them - can be assumed to be stable.

Determining a suitable investment term for stable and (usually) zero-rate NMDs is one of the biggest challenges in IRRBB. If a bank invests too short and rates fall, its net interest income (NII) will decrease and, in extremis, could fall to a point where it no longer covers even the operational costs of servicing the deposits. Equally, investing too long could put the bank at a major competitive disadvantage should rates rise and rival banks had invested shorter – i.e. the “mistake” BOA is said to have made.

In a banking book, it has – at least until recently – usually been accepted that rate “views” should not form part of the decision-making process. So called, “positioning”, to take advantage of some personal opinion as to the direction of rates is really code for the bank saying it knows better than the market. When BOA locked in at 2.4%, it was in reality, positioning itself for the rate rises that were generally expected, at that point. Clearly some people had different opinions, but they must have been a minority or else the market rates available would have reflected their view.

In essence, those who invested shorter were simply betting that rates would rise more quickly than the market then believed. The fact that they were proved right in this instance, does not mean they were any more prudent – indeed, it was quite the reverse. Had some unforeseen “event” such as another pandemic then caused another large unexpected fall in rates, then BOA’s strategy would now seem rather sensible and would probably be earning praise from the very people now criticising it.

If, as is argued here, it is agreed that personal rate views ought to be put to one side, what then should determine the investment term or duration of any structural hedge? There are really two objectives:

- To protect earnings from short to medium-term volatility – the longer the investment term selected, the more this objective is achieved.

- To ensure that the bank’s returns, in the medium to longer-term, do not start to diverge materially from whatever the general level of interest rates might be in the future. This objective is achieved usually by opting for an investment term somewhat shorter than might initially be suggested from an estimate of when (if ever) the underlying deposits will re-price.

Therefore, a balance needs to be struck, and up until 2008/09 most banks seemed to have selected investment terms of around 5 years. As a result, they largely stabilised earnings but, at the same time, kept their returns more or less in line with one another, albeit on a slightly lagged basis with the prevailing level of interest rates. Mechanically, this involved spreading the maturity of the assets quite evenly over 10 years, so that on average, a constant maturity of 5 years was maintained.

As only one tenth of the portfolio would re-price each year (i.e. be invested for a further 10 years), any income volatility from rate movements was minimised, and at the same time, the overall return on the whole portfolio would gradually rise or fall in line with the general level of interest rates.

For such a strategy to work, it is important that the original investment term – whatever it might be – is maintained regardless of any subsequent changes to the shape of the yield curve. The objective, after all, is to hedge against the downside risk of rates falling below the level implied today by the yield curve. But at the same time, this means forgoing any upside from rates moving higher than is implied. While the yield curve may, in practice, prove to be a poor predictor of what rates will actually do, it does nevertheless constitute a set of prices that are currently available. To suggest that BOA’s continued investment in long-dated assets when rates were lower was somehow a “missed opportunity” makes as much sense as saying that hedging a fixed-rate loan represents a “missed opportunity” to benefit from any possible fall in rates.

Bank treasurers already have a lot on their plates – they are funding their banks, ensuring there is sufficient liquidity in the event of stress, maintaining an optimum level of capital and minimising avoidable exposure to all market risks.

Adding to this list an expectation that they should also be able to predict correctly what interest rates are going to do – and then support this with huge positions – is not only unreasonable but positively dangerous. Unless they have access to crystal balls, about half will get it right and earn plaudits from the “experts”, but the other half will, at best, be labelled failures and, in a worst case, could even end up bringing their banks down.

If banks – or their investors – really want to place bets on interest rates, these should at least be restricted to their trading books so that if, and when, losses occur, they do not impact either the wider bank or the whole financial system. To suggest, effectively, that banking book positions should be managed as though they were trading book positions seems to amount to an argument in favour of gratuitously tossing yet another risk factor into a business model that is quite risky enough as it is.

Paul Newson

Share "Bank of America: In Defence of Structural Hedging" on