Introduction to Bank Analysis II

January Carmalt

20 years: Research & banking

In this second part of the two part series, January explains how to look at an income statement to determine a bank's profitability.

In this second part of the two part series, January explains how to look at an income statement to determine a bank's profitability.

Subscribe to watch

Access this and all of the content on our platform by signing up for a 7-day free trial.

Introduction to Bank Analysis II

5 mins 25 secs

Key learning objectives:

Explain what a bank’s income statement consists of

Understand the meaning of its line items

Overview:

A bank’s income statement can appear complicated at first glance. However, it can be very simply analysed with an understanding of the operations and goals of a bank. Important measures include net interest income and loan loss provisions.

Subscribe to watch

Access this and all of the content on our platform by signing up for a 7-day free trial.

What is the income statement?

The income statement, or statement of Profit and loss is unique in banks and differs from that of a corporate primarily in how its core profitability is measured. As we’ve established, the primary business function of any bank is lending and borrowing, earning interest with the former, and paying on the latter, taken together to constitute the net interest income. The other two major line items we note are firstly, net fee and commission income, derived from various bank activities, including investment management, insurance, payments processing, etc. And secondly, net trading income, again derived from a bank’s principal market making, or trading activities.

What are the operating costs in an income statement?

Below the profit line are operating costs. These consist of the following:

- Staff and administrative expenses (the largest component)

- Depreciation

- Amortisation

- Other expenses

What is the cost-to-income ratio?

Total income less expenses produces a bank’s net profit, and with this we have our first major profitability ratio, the cost-to-income ratio, calculated by dividing total costs by total income. Note this is entirely unique from how a corporate measures profitability using EBITDA. A consequence of banks’ fundamental business model, the largest expense is interest income, incurred via deposit gathering and debt issuance, and so it’s necessary to deduct this line item above net profit in order to get a clear picture of core profitability.

How do banks cut costs?

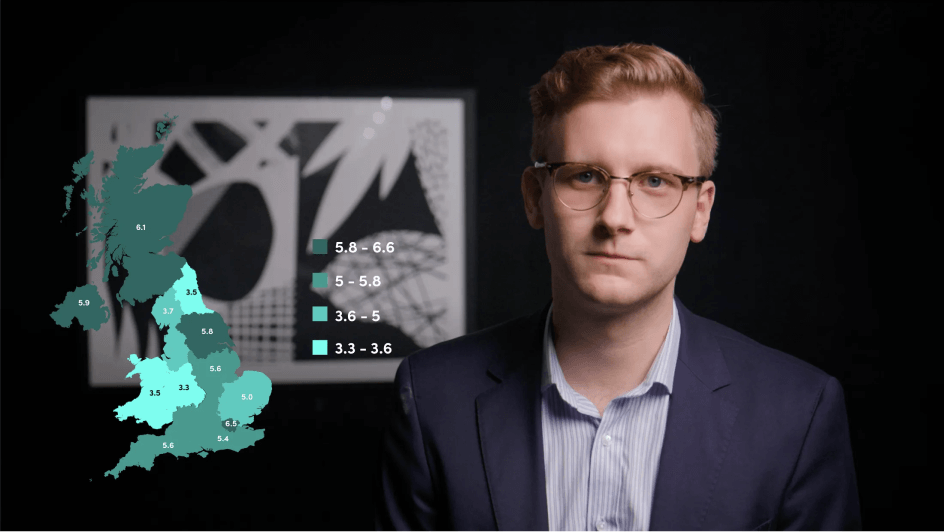

To improve the cost-to-income ratio and underlying profitability, banks are always seeking new ways of cutting costs, be it via increasing the automation of payments, staff redundancies or what we increasingly witness, the ever declining presence of high street branches as more and more systems and operations move online. During times of economic stress, cost-cutting is a priority as a means of upholding profitability as income declines and asset quality falls.

What is the net interest margin, and how do we calculate it?

Sticking with net interest income, we can also derive a bank’s Net interest margin, or NIM, which illustrates how profitable a bank’s loan book is, by calculating net interest income by gross lending. This is normally in the low single digits, typically lower in times of low interest rates, inching upward at times of higher interest rates.

What are loan loss provisions, and what do they tell us?

Moving below operating profit are a bank’s loan loss provisions. These may also go by other nomenclature, including impairment provisions, allowances for bad debts, etc. These are defined as; a picture of asset quality and a bank’s overall ‘cost’ of lending. These are provisions deducted from income below net profit to cover future losses from non-performing loans and/or other assets, the NPLs and/or NPAs of a bank.

Loan loss provisions are an important leading indicator of weakening or improving credit quality, trending upwards during times of pending and present economic stress, falling as economies and thus lending conditions improve. Loan loss provisions, or LLPs, may also be used to smooth earnings, increasing during times of higher overall profitability in order for a bank to build up loan loss reserves in anticipation of future economic headwinds and increasing NPLs. The Loan loss provisions on the income statement are then added to overall loan loss reserves, highlighted earlier. This can confuse some people, loan loss provisions, or impairment provisions, are on the income statement. These are added to, or deducted to the loan loss reserves, a balance sheet item. Therefore, loan loss reserves, which can normally be found in the notes of the balance sheet, should rise (or fall) by the sum of provisions the bank has deducted (or in some cases, added back) to a bank’s underlying operating profit.

What are the other profitability indicators?

These are not terribly unique from corporates, including Return on assets, or ROA, Return on Equity, or ROE, earnings per share and so forth. However, the delta between reported ratios of a bank, and of a corporate can vary vastly. Particularly looking at ROA, which for banks may appear woefully weak, this is due in part to what we discussed earlier, the sheer size of banks’ balance sheets making for optically paltry profitability indicators.

Subscribe to watch

Access this and all of the content on our platform by signing up for a 7-day free trial.

January Carmalt

There are no available Videos from "January Carmalt"