Impact of Agriculture on Biodiversity and Soil Regeneration

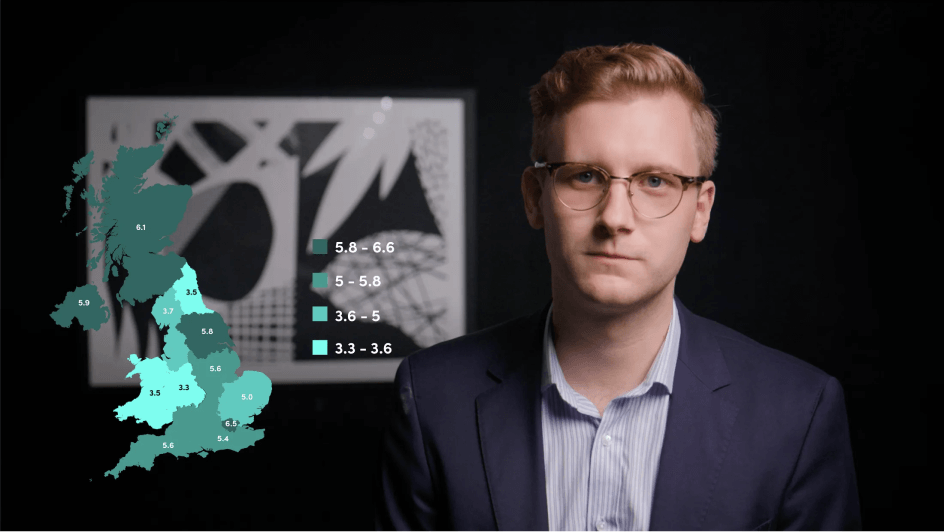

Oliver Knight

15 years: Agricultural specialist

It was said that food production could never keep up with human demand. For a while, we’ve managed to prove that wrong. But what have the effects of mechanisation and artificial fertilisers had on soil and nutrition? Join Oliver Knight as he guides us through these pressing issues.

It was said that food production could never keep up with human demand. For a while, we’ve managed to prove that wrong. But what have the effects of mechanisation and artificial fertilisers had on soil and nutrition? Join Oliver Knight as he guides us through these pressing issues.

Subscribe to watch

Access this and all of the content on our platform by signing up for a 7-day free trial.

Impact of Agriculture on Biodiversity and Soil Regeneration

11 mins 40 secs

Key learning objectives:

Learn how agricultural production has developed

Identify the impact of agricultural production on climate and biodiversity

Understand the importance of soil

Overview:

The Agricultural Revolution ushered in an explosion of growth in food production. This started in the UK in the 18-19th centuries, which introduced new management techniques to increase production, along with the Haber-Bosch process, which developed a method for producing synthetic ammonia. But this has come at the cost of biodiversity, nutrition and soil health. Healthy soil is central to a sustainable and healthy food production system and also represents one of the largest opportunities related to carbon in farming.

Subscribe to watch

Access this and all of the content on our platform by signing up for a 7-day free trial.

What developments have we seen in agricultural production?

The agricultural revolution in the UK in the 18-19th century introduced new management techniques to increase production e.g. crop rotations (for example, the Norfolk four-course system), selective breeding (for livestock and crops) and investment in drainage. There was also the Haber-Bosch process, in the early 20th century, which developed a method for producing synthetic ammonia, used to apply synthetic nitrogen fertiliser into agricultural systems.

The past century has seen great leaps in mechanisation, leading to huge increases in the scale of farming operations. As well as advances in plant and animal genetics, leading to selective breeding for production improvements, for yield, milk production, meat density, and disease control.

What have been the consequences of agricultural developments on the ecosystem?

We now have much greater areas of land converted to agriculture. Larger fields for larger machinery and efficient production have led to the removal of hedgerows and field margins, reducing important habitats. We have seen significant reduction in diversity of crop and livestock genetics, of plant species and of animal and insect species. Herbicides and pesticides have devalued ecosystems, removing valuable natural predators, representing a huge loss of biodiversity, impacting the food production system.

Artificial fertilisers have left ecosystems hooked on artificial inputs, not sourcing natural ones. Think of a high-performance athlete – a little extra nutrition helps improve performance but hugely concentrated artificial levels lead to dependency on artificial help, stunting other natural growth.

One of the greatest areas of concern is the depletion of soils. Some estimates state we only have 60-100 harvests left. Intensive farming practices, mining without regenerating soil resources, intensive use of artificial inputs, lack of diversity and lack of protection (or soil cover) have seen topsoils diminishing and in some cases resulting in soil (and carbon) blowing away in the wind.

Production models have not taken into account their consequential effects, or externalities, leading to pollution of waterways (for example with nitrates, slurry and pesticides), and emissions in the form of nitrous oxide (from synthetic nitrogen) and carbon released from depleted soils.

Lack of diversity, the heavy use of synthetic inputs and accelerated production techniques have also led to reduced nutrition in food. For example, some claim one orange in the 1950s had the same amount of vitamin A as 21 oranges today. Grain-fed chickens in industrial systems contain five times less omega-3 than 1970. Similarly, for Scottish farmed salmon, double the portion size was required in 2015 compared to 2006 to obtain the same levels of omega-3.

Why is soil important?

Healthy soil is central to a sustainable and healthy food production system. Likewise, soil represents one of the largest opportunities related to carbon in farming.

Soil degradation can lead to a combination of the following: poor fertility, poor infiltration of water, compaction, weeds, reduced yields, high input costs, plant diseases, invasive pests, erosion, declining profits.

How does soil work?

Plants use the power of the sun to combine carbon dioxide and water to form simple sugars, releasing oxygen (photosynthesis). These sugars are the building blocks of life as plants use them for plant growth. But plants also provide carbon to soils.

So plants collect sunlight and recycle carbon, and feed soil microbes. Microbial activity then drives soil aggregation (or growth), enhancing soil structure, improving aeration, infiltration and dramatically increasing water holding capacity.

Soil is home to a highly complex network of living organisms and microbes, which are microorganisms. It is estimated that 90% of the 1 trillion microbial species on earth are yet to be discovered.

These microbes include bacteria (which feed other microbes), nematodes (which kill pests and recycle nutrients), protozoa (which turn nutrients into minerals), earthworms (which break up decaying matter and improve soil structure) and fungi.

Mycorrhizal fungi are particularly interesting for the purpose of this discussion. They act as an extension of the plant root, to the point they can increase the root mass of a plant by up to 80%. They acquire nutrients for the plant in exchange for carbon, via an intelligent exchange. We know little about this, but we know plants send complex chemical signals through their roots to source the right minerals for their needs.

The subterranean carbon exchange from plants also feeds humus. This is a stable, long-lived form of organic carbon - carbon derived from living matter - which can live deep in the soil for thousands or millions of years. A significant long-term, natural carbon storage, which also provides significant water-holding capacity.

Harnessed correctly, this can result in a powerful positive feedback loop. The sun’s energy drives photosynthesis in plants, which in turn provide liquid carbon to soils, which fuels microbes, which provide nutrients and minerals back to the plant, which grows and drives more photosynthesis, also generating nutrient-dense food. And the carbon exchange is used to build humus, the long-term carbon store.

Why can synthetic fertilisers be a problem?

Synthetic fertilisers interrupt the carbon exchange. They provide free nutrients, reducing the requirement for plants to trade carbon for nutrients and minerals from microbes. They also only provide limited nutrients - not the full range of minerals. This can reduce the nutritional value of food and reduce the carbon provided for microbes, limiting their population growth.

How can we regenerate soil?

Gabe Brown’s book, From Dirt to Soil, lays out five steps for soil regeneration.

- Minimal disturbance. This means avoiding breaking up complex soil structures.

- Diversity. Meaning growing different species and different root systems.

- Cover or soil armour. This means protecting the soil by maintaining continuous cover, with cover crops in between growing cycles.

- Maintaining living root systems as much as possible, which drive the plant carbon-for-nutrient exchange, feeding the soil.

- Integrated animals. Livestock graze the crops or grasses, which in turn stresses the plant, forcing more carbon for nutrient exchange in the soil. They also graze away diseased leaves and fertilise the soil with organic matter.

Subscribe to watch

Access this and all of the content on our platform by signing up for a 7-day free trial.

Oliver Knight

There are no available Videos from "Oliver Knight"