What was the impact of the financial crisis on emerging markets?

Emerging markets and Asia emerged relatively unscathed from the 2008 subprime crisis. This is because the epicentre of the crisis was in the developed countries’ financial markets. Asian economies and financial markets were caught up in the liquidity driven global boom in the run up to the crisis. However, Asian investors were not overly exposed to those innovative financial instruments that ultimately precipitated the subprime crisis.

Asian economies were hit through exports and capital flows. Asian asset markets corrected along with their global peers as heightened investor risk aversion led to capital flight. Asian exports collapsed as the world slid into recession, and some countries experienced a technical recession.

How did monetary policies impact emerging markets?

The policies of the ECB, BoE and BoJ have been particularly damaging for the world economy, all the way until 2016. The extraordinary monetary policy measures had two objectives. Firstly, to stimulate domestic demand in these countries by encouraging borrowing to support investment and consumption. Secondly, to drive down their currencies to give their exporters a competitive edge.

As US dollar borrowing costs collapsed, US dollar borrowing by non-US, non financial corporates surged. It made good business sense to borrow abroad. US dollar borrowing costs collapsed after 2009 and have stayed significantly below prevailing domestic interest rates for much of the past eight years. The desperate chase for yield meant foreign investors were willing creditors. Credit-worthy companies found foreign lenders eager to lend, and so did companies which, in a normal interest rate environment, would be deemed risky and un-credit worthy.

What were the implications of monetary policy normalisation for emerging markets?

The good news is the global economy and Asian economies are in good shape. We do not see monetary policy normalisation derailing growth. The bad news is that US interest rates are rising. By historical standards monetary policy will still be accommodative but the unwinding of quantitative easing, trade tensions and mounting concerns about external debt sustainability are sending shudders through emerging markets.

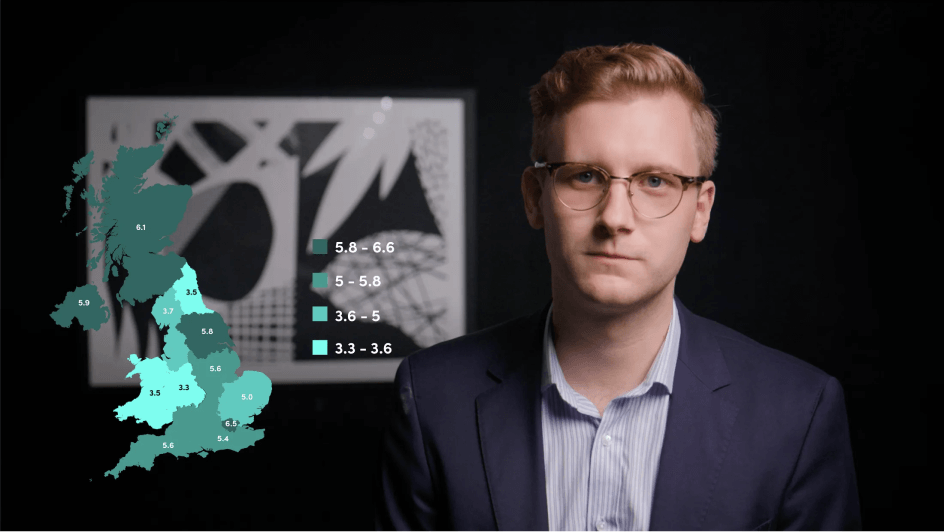

Markets are becoming less tolerant of growing current account deficits, falling foreign-exchange reserve coverage ratios and political instability. Particularly hard hit have been Turkey, Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, Venezuela and South Africa – the EM 6 group of countries. In Asia, the Philippine peso, Indian rupee and Indonesian rupiah have come under pressure due to mounting concerns about their growing current account deficits. EM external debt has also risen sharply in the era of ultra-low US dollar borrowing costs.

Will ending Quantitative Easing create a crisis in emerging markets?

A default on, or a widespread sell off of, corporate foreign currency bonds would hit Venezuela and Turkey hard and would likely lead to a full blown balance of payments crisis and economic recession. Mexico is not looking that safe either and could easily become the next target. If investors are worried about EM6 countries, it is with good reason. Asia is a different story altogether. Regional fundamentals are strong. There are a few warning flags but none that suggest that an external debt crisis is about to engulf the region.

In Asia the immediate risk of non-repayment is small and the ability to withstand capital flight due to contagion is high. Asia can comfortably cover short-term debt by dipping into foreign exchange reserves, in the event that foreign investor risk aversion causes international capital markets to dry up. The only exception being Malaysia.

EM stock market volatility will persist and external debt sustainability is an issue for some EM economies. EM6 group are looking vulnerable to rising US interest rates. However we are not at this stage forecasting a full blown EM external debt crisis. The world economy, including Asia, is growing strongly and can absorb higher interest rates, provided that the normalisation of monetary policy in the advanced world is gradual. Asia is looking good. Fundamentals are strong. External debt has risen, but is sustainable.