Is Quantitative Easing Still Necessary?

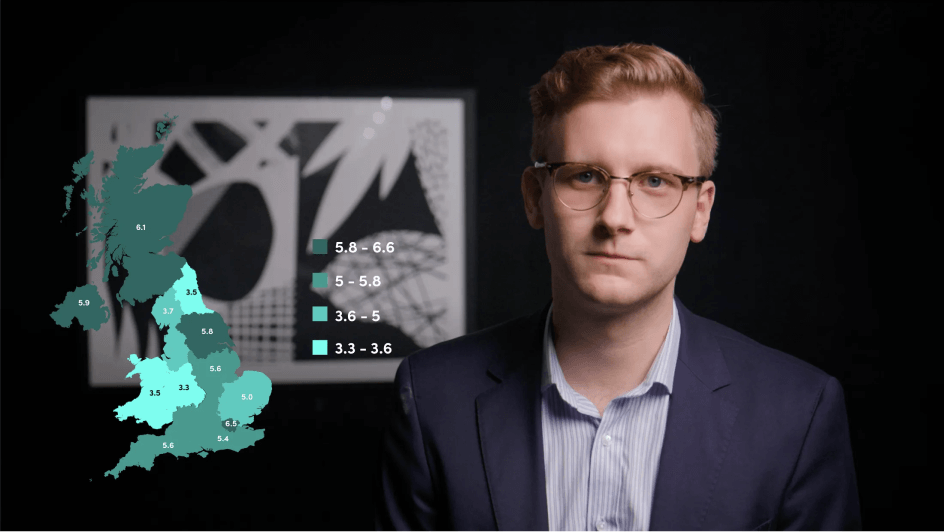

Trevor Williams

25 years: Macroeconomist in banking

Trevor talks us through his thoughts on central bank monetary policy and the potential consequences of the reversal of quantitative easing.

Trevor talks us through his thoughts on central bank monetary policy and the potential consequences of the reversal of quantitative easing.

Subscribe to watch

Access this and all of the content on our platform by signing up for a 7-day free trial.

Is Quantitative Easing Still Necessary?

11 mins 17 secs

Key learning objectives:

Understand the impact of quantitative easing on the economy

Outline the risks of ending QE

Understand the implications of returning to normal monetary policies

Overview:

Monetary policy was stretched to new levels of involvement during the crisis of 2008. Central banks resorted to policies such as Quantitative Easing (QE) that have never been seen before. QE, asset purchases by central banks, boosted the confidence of financial markets. It signalled a policy of loose rates and rebalances portfolios from low risk to high risk as it boosts market liquidity. In doing so, it creates a greater supply of money.

Subscribe to watch

Access this and all of the content on our platform by signing up for a 7-day free trial.

Subscribe to watch

Access this and all of the content on our platform by signing up for a 7-day free trial.

Trevor Williams

There are no available Videos from "Trevor Williams"