The Irish National Asset Management Agency (NAMA)

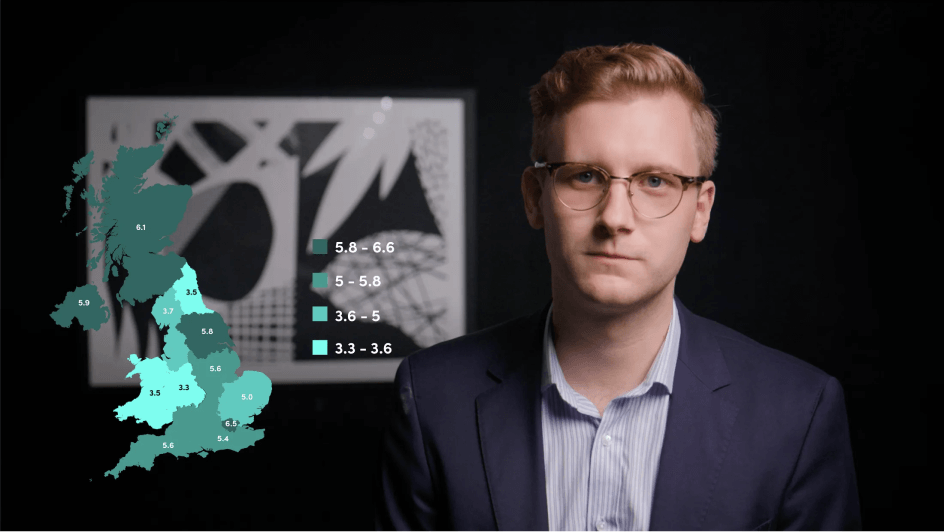

Michael Torpey

30 years: Treasury & banking

The National Asset Management Agency was a vehicle designed to purchase loans from banks at their long-term value. Michael explains how these valuations were calculated and provides his thoughts on the effectiveness of the vehicle and the decisions that were made surrounding it.

The National Asset Management Agency was a vehicle designed to purchase loans from banks at their long-term value. Michael explains how these valuations were calculated and provides his thoughts on the effectiveness of the vehicle and the decisions that were made surrounding it.

Subscribe to watch

Access this and all of the content on our platform by signing up for a 7-day free trial.

The Irish National Asset Management Agency (NAMA)

6 mins 44 secs

Key learning objectives:

Explain why NAMA was established

Explain the criticisms of the loan-by-loan valuation approach

Describe NAMA’s legacy

Overview:

Ireland setup NAMA to allow its banks to move on from their bad loan problems. The government bought loans from the banks, assessing their value on a loan-by-loan basis. Although NAMA was kept off the country’s balance sheet, the state’s guarantee of the agency’s bonds had a negative impact on its credit quality. NAMA succeeded in allowing banks to resume new lending and some argue it should have been extended.

Subscribe to watch

Access this and all of the content on our platform by signing up for a 7-day free trial.

What is NAMA?

The Irish public authorities were concerned that with a complete absence of liquidity in the market, market forces could not be relied upon to establish a base that bore any resemblance to a true underlying or long-term market value for the property loan assets that dominated the Irish banks’ balance sheets.

NAMA was established as a vehicle for the government to purchase the loans at their long-term value from the banks. Without the agency, the authorities would not have been able to identify the actual capital position or shortfall of the banks, leaving them unable to confidently address the problem.

With the Bank Guarantee already leaving the State very stretched, it was a very difficult path. But the alternative was a total collapse of the Irish financial system. To avoid further inflation of the national debt, NAMA was structured as a non-State entity. It financed its purchases of the land and development loan assets by paying for them with State guaranteed bonds.

While NAMA was kept off the government’s balance sheet in technical terms, the State guarantee of NAMA bonds was an added encumbrance with a consequent impact on the credit quality of the State.

How effective was the loan-by-loan valuation approach?

The valuations applied to loans acquired by NAMA were prepared ‘bottom up’ and were intended to amount to their long-term values. This was time-consuming and the values arrived at were heavily dependent on the assumptions made.

Many felt the State was giving additional support to the banks by paying too much for the loans. The banks, on the other hand, felt that they were being forced to sell cheaply.

However, as we near the final disposal of the loan assets acquired by NAMA, it can be seen that the State is set to record only a modest surplus from the process. This suggests that the valuations arrived at, proved to be robust.

What is NAMA’s legacy?

NAMA was widely resented, therefore, NAMA Phase 2, the take-on of loans of less than €20 million in size was not progressed by the new Government that came into power in April 2011. The banks were left with a substantial volume of such loans with individual ticket sizes below €20 million.

It is now evident that the loans that had gone to NAMA were history from the point of view of the banks and did not interfere with those banks resuming lending once they were restructured and recapitalised.

In contrast, the loans which did remain on the banks’ balance sheets operated as a major hindrance, as the banks attempted to normalise. Many now believe that NAMA should have been extended to land and development loans in the €5m to €20 million range. This would have greatly reduced the level of non-performing loans carried forward by the restructured and recapitalised banks and would have aided a more rapid normalisation, post-crisis.

Subscribe to watch

Access this and all of the content on our platform by signing up for a 7-day free trial.

Michael Torpey

There are no available Videos from "Michael Torpey"