The Sterling Bond Market

David Carmalt

20 years: Debt capital markets

David outlines what a bond is, before describing the Sterling bond market, its investors and its impact on the broader economy.

David outlines what a bond is, before describing the Sterling bond market, its investors and its impact on the broader economy.

Subscribe to watch

Access this and all of the content on our platform by signing up for a 7-day free trial.

The Sterling Bond Market

10 mins

Key learning objectives:

Define a bond

Understand who are the investors and the issuers

Explain the size and impact of the Sterling bond market

Overview:

The Sterling bond market is attractive to UK and non-UK issuers and investors alike. Although the sterling bond market appears small, relative to the global bond market, it has a large impact on companies and governments who require additional capital for their spending and regulatory needs.

Subscribe to watch

Access this and all of the content on our platform by signing up for a 7-day free trial.

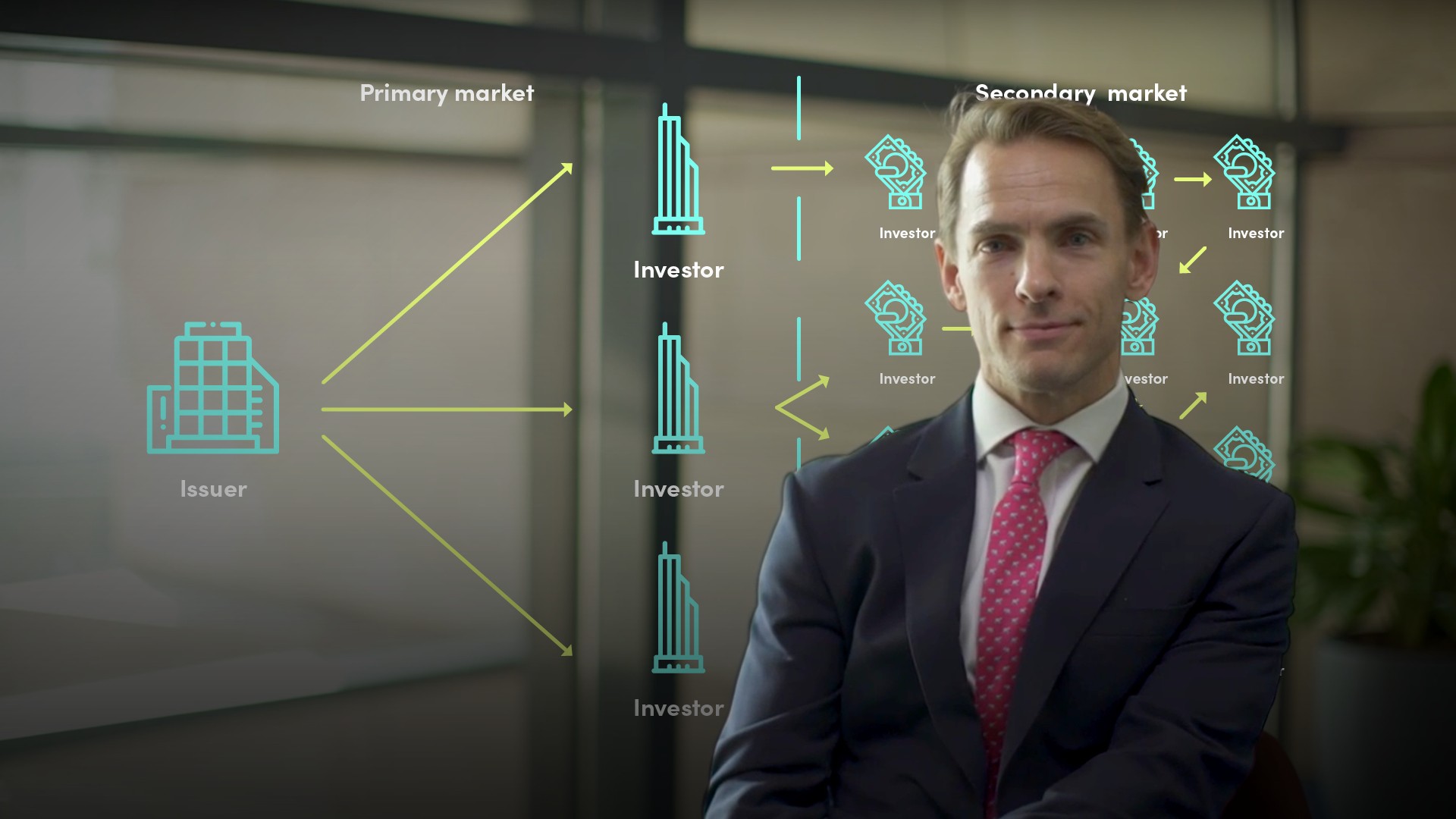

What is a bond?

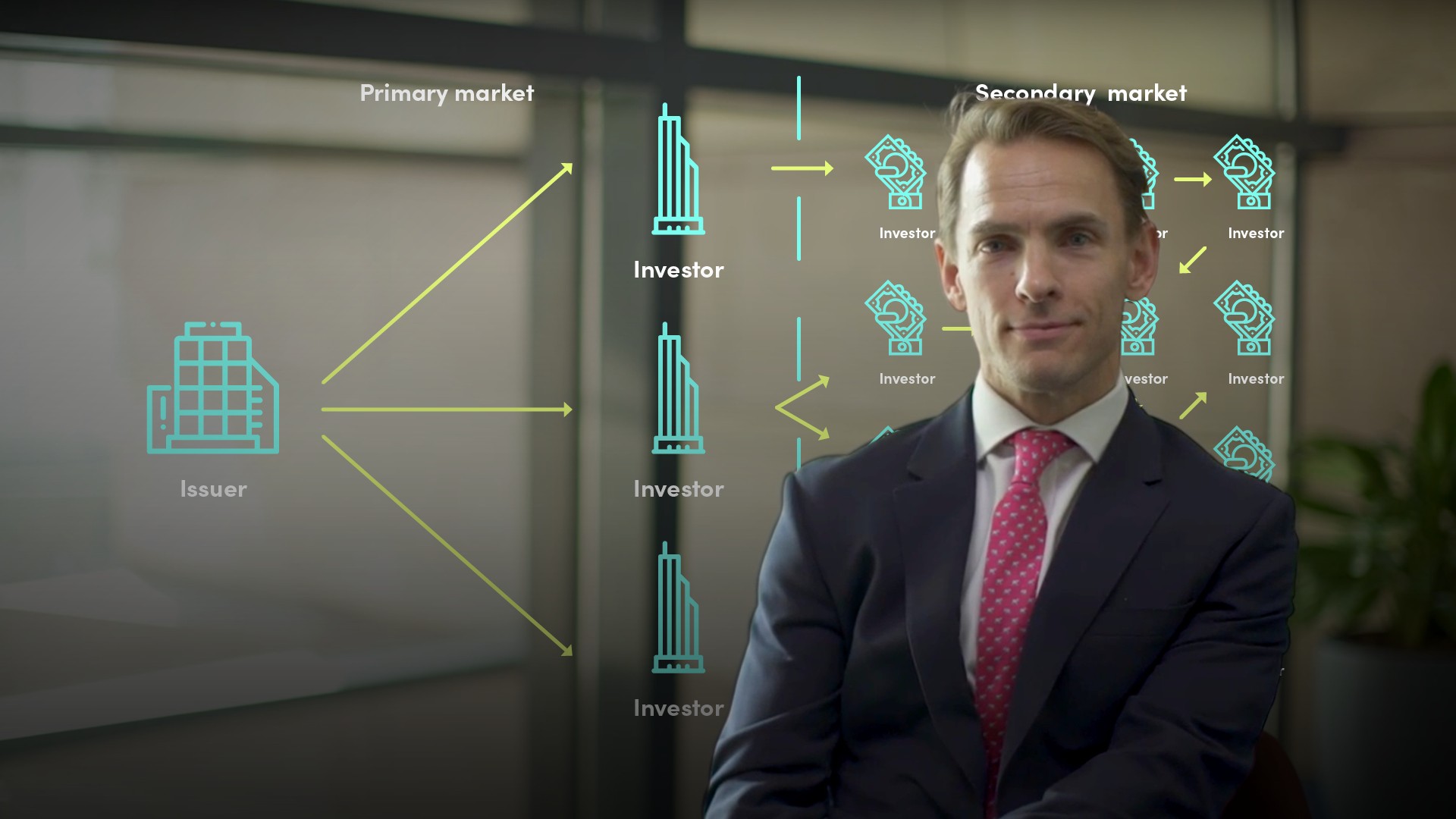

A bond is effectively an IOU between a borrower (the issuer) and an investor.

Bonds are issued with a defined maturity date, although there are exceptions to this. While bonds are often referred to as “fixed-income instruments”, a significant proportion of bonds issued do not have predetermined fixed-rate coupons, or interest payments. All interest payment dates are fixed in advance but the actual amount of the interest on some bonds can vary as they are paid based on a floating rate of interest i.e. it can change depending on movement in an underlying reference benchmark.

Whether a new issue is structured as senior unsecured, asset-backed, subordinated or convertible, will depend on what purpose that borrower is raising funds for.

How large is the global bond market?

Globally, there are over US$62 trillion of bonds outstanding, which is basically the same as the current estimate of the global equity market, which stands at US$65 trillion.

Global bond volumes by currency are dominated by US$, which remains the only global “benchmark currency”. The depth of the US$ bond market is driven not only by US issuers and investors, but also by issuers and investors across the world, who either have assets/liabilities denominated in US$ or currencies pegged to US$.

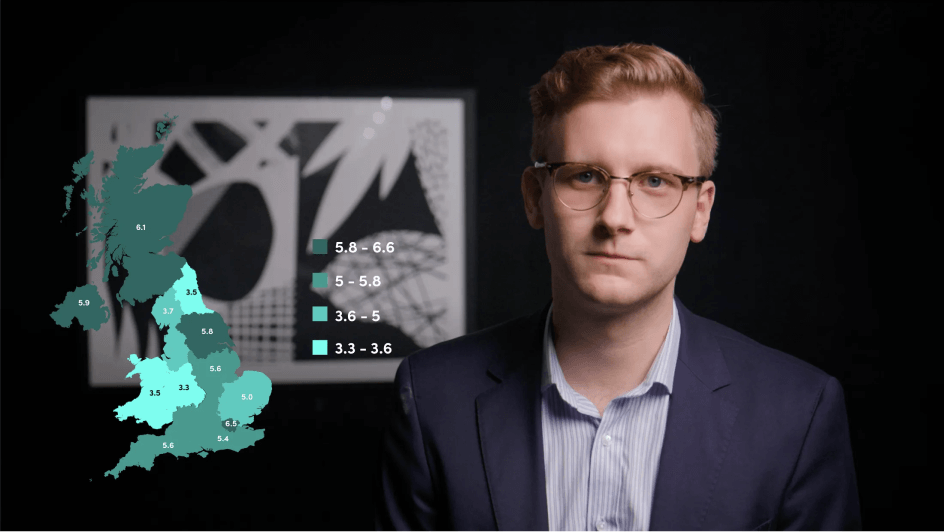

How big is the Sterling bond market, and how did it begin?

The Sterling bond market is equivalent to US$1.5tn or 2.5%. It emerged in 1980, which was the first full year after exchange controls were lifted. In that year, excluding UK government bond issuance, only £750m was issued by financial institutions and corporates. Those numbers rose rapidly from then, such that in 1988 this number was closer to £17bn – but with the extreme recession which struck in the late ‘80s, the Sterling bond market almost died out.

Post-recession, the market re-emerged as the “euro sterling” market, becoming deeper and more complex by necessity as it competed with the nascent Euro corporate bond market. The emergence of large UK pension funds which were buying significant volumes of fixed income securities was fuel for this growth, and laid the foundations for the types of issuance that we see today.

Why do non-UK issuers tap into the Sterling bond market?

It isn’t only UK-domiciled issuers that will borrow in the Sterling market, while they will always dominate, last year 47% or £54bn was issued by non-UK companies with German and US issuers leading the pack.

These non-UK issuers tap into the Sterling bond market for a number of reasons: these companies may be large multinationals which have Sterling denominated assets to fund; they may be looking for the “cheapest to deliver” market to issue in a certain maturity and Sterling may be most attractive to them on a certain day; or they may be a large borrower in global markets which is keen to spread its issuance over a broad range of currencies and benefit from the investor diversification that this approach ensures.

Who are the investors buying Sterling bonds?

Fixed income investors can broadly be put into three categories:

- “Real money” - asset managers, pension funds and insurance companies, i.e. funds which tend to have a longer term buy and hold approach to investing

- Bank treasuries - liquid asset portfolios of banks, building societies and the like, which look for a return on their money but which typically look for very defensive assets in which to invest

- Hedge funds or “alternative asset managers” - this category can encompass a wide range of investor types, but typically these would take a shorter term view of investing, and could look at a range of different hedging strategies to maximise returns

The largest investors tend to be real money and some of the alternative asset managers, a host of whom will run fixed income portfolios which stretch into the tens of billions of dollars.

What is the impact of the Sterling bond market?

On a bank - typically, deposits alone will not be enough to fund lending to retail customers; banks will also need capital in their balance sheet to satisfy regulators that they have enough of a buffer to absorb losses in the event of a crisis. Much of this buffer is typically made up of debt instruments.

On an insurance company - they also have a regulatory requirement to achieve, similar to a bank. To satisfy this requirement, much of this is done via the bond market.

In a corporation - liquidity may be needed in the form of bonds. Hybrid capital (also a type of bond) may be needed to achieve a certain equity credit to achieve a rating agency hurdle.

On a government - it is unlikely that governments are receiving enough tax from individuals and companies to reach their spending targets, so governments raise debt via bonds. The same is often the case for local authorities, universities, and even individual hospitals.

Subscribe to watch

Access this and all of the content on our platform by signing up for a 7-day free trial.

David Carmalt

There are no available Videos from "David Carmalt"