Uncontrollables - coping with 'dis-order'

Hans-Kristian Bryn

35 years: Strategic risk management and governance

Geopolitical risk is now regularly on the Board agenda, joining climate, environmental, health, cyber and technological change, not least disruption by AI.

As many New Year articles have alluded to, 2024 will undoubtedly be another year we will look back at to recognise that the uncertainty faced at the beginning was of a different shape and magnitude to that at the end. There are elections for around 4bn people across 70 countries, wars and trade conflicts. Geopolitical risk is now regularly on the Board agenda, joining climate, environmental, health, cyber and technological change, not least disruption by AI. In this article, we will focus on how management and the Board may respond to these issues but from the angle of when uncontrollable factors become permanent features that may cause the layout of the chessboard to change.

We define “uncontrollables” as factors that the company has no or a minimal impact on. If, for example, a government legislates against use of a critical resource or trade relationship it is hardly management’s fault that profits are hit as it is outside of what can reasonably be controlled. But the predictability of uncontrollables shift and there comes a point when not including an uncontrollable factor in the planning and execution of strategy becomes a failure to take responsibility for.

Uncontrollables are hence a key consideration for both risk management and the success businesses reward and we are seeing signs of more permanence in more uncontrollable factors than ever before.

Remuneration responses to long-term shifts of uncontrollable factors

Perhaps one of the best illustrations of how long-term shifts of uncontrollable factors require a different approach to that of ad hoc challenges can be found in compensation and benefits. Where a temporary market situation may lead to lower incentive pay-outs and even headcount reductions, a long-term shift will likely mean changes to reward strategy, processes and governance. For example, a long-term disruption to the logistics of moving goods around the world doesn’t just result in input prices going up and decisions on how to pass on those costs, but it may also require a change to how remuneration decisions are made, in particular how strategic shifts are rewarded.

The most common long-term uncontrollable impacting reward is inflation, where prices move up as the purchasing power of money weakens. As it increases, inflation impacts remuneration in many different ways, notable being: first, balancing cost-of-living increases to maintain employees’ standard of living against society’s demands on not fuelling inflation and shareholders’ increased costs; second, that wage inflation becomes more differentiating as scarce labour not only can, but increasingly chooses to, exercise its bargaining power; and, third, that differences in inflation rates, such as those between countries or sectors, need to be managed. Inflation exposes a company’s weaknesses in relation to a range of variables like productivity and sourcing of inputs and expertise, which means that it becomes harder to paper over the cracks.

However, if companies only react to a new situation they will be at a disadvantage. When there is a long-term shift in the nature of uncontrollable factors, businesses need to review the approach to reward and consider both what new information is required for decision making and whether new structures or re-balancing of reward is needed. For example, higher inflation rates now lead to higher percentage increases in remuneration levels than companies have seen for a long time. This means that the distinction between merit, promotion and cost of living increases for salaries become important again and that in turn means that decisions on differentiation between employees can either generate strategic advantage or a struggle for survival. Inflation puts pressure on the affordability of salaries and benefits, which should make Boards reflect on both workforce structures and the proportions of fixed and variable pay, not least for executives in countries where investors try to contain salary increases to within the average rate of salary change.

Variable compensation, like bonuses and long-term incentives, is even more sensitive to shifts in uncontrollable factors. It is not only impacted by the points above, not least as variable pay tends to be a function of the base salary, but most performance measures that determine the value of incentive outcomes are very sensitive to how uncontrollable factors are treated. This leads to frequent points of friction between Board and management as to the common understanding of how performance is measured, in particular in terms of how changes to variables like inflation, currencies, regulations and supply chains are included or excluded from the calculations. Or to put it another way, when do executives and employees align with the experience of shareholders and when do they simply get paid for the jobs they do? The answer to that may seem straight-forward for many, but most Boards that spend time on the question will recognise that it requires answers that are grounded in a reward philosophy which is clearly articulated and communicated with both participants and other stakeholders so that there is a common understanding. To address the potential impact of uncontrollables, companies should therefore consider reviewing:

- The remuneration philosophy to ensure that there is a clear approach to uncontrollables and update remuneration policies accordingly;

- Processes for setting salary budgets as well as both levels and performance targets for incentives; and

- Communications with employees and other stakeholders.

Risk planning/management challenges – being prepared

Both newspapers and digital platforms are full of articles that set out the case for why we are living with ‘unprecedented’ geopolitical uncertainty and by inference increased uncontrollables. It is tempting to view these developments as another set of stand-alone risks that are hitting organisations and making it much harder to plan and execute. However, there is also a need to step back and consider whether some of the developments we are facing, like sustained higher levels of inflation or concurrent geopolitical hotspots, represent systemic shifts from one state to another.

If the latter is the case, it becomes clear that our planning models and assumptions have to develop and respond to a new situation where the chessboard and rules of the game have shifted. Our planning and risk models need to perform in a world of ‘dis-order’ and incorporate a mind shift from looking at individual incidents or risks to multiple and linked risks which have longer term implications for strategic positioning and risk management.

We observe that one of the risk areas that is getting more attention due to the impact of uncontrollables is supply chain risk. As a consequence of the adverse impact on supply routes from multiple geopolitical hotspots, portfolio concentrations such as supplier company, supplier region and transport routes are becoming more prominent considerations. This is leading many companies to more thorough evaluations of solutions, such as nearshoring, changes to supply routes and diversification of some of the existing concentration risks.

From a business management and oversight perspective, the key question is clearly ‘so what can we do about it?’ In fairness, none of us can do much to influence the underlying drivers of the geopolitical uncertainty or the resulting uncontrollables, so the focus therefore has to be on how businesses build resilience by planning and being prepared for when the risks crystalise.

As a first step, companies need to consider the relevance and impact of these risks in the context of their business strategy, operating model, footprint and context. In an earlier article, we have made the case for a broadening of the consideration of context as set out in the diagram below:

We expect that leading companies are already well underway with the planning activities for uncontrollables, however, we are also confident that many businesses are still in the starting blocks in terms of responding to long-term shifts. The current risk planning approaches tend to have been developed for more benign contexts than what we are facing, hence changes will be required to incorporate the impact of uncontrollables.

One of the questions we often face is ‘how should businesses plan for such unpredictable and uncertain risks?’ A great question which in itself implies that the answer is less about looking at risks in isolation or using existing approaches. These are risks that require management and the Board to apply more in-depth analysis.

An approach (and there certainly isn’t one size that fits all) that incorporates most of the characteristics below is likely to generate a better discussion and hopefully lead to more considered responses;

- Apply a scenario-based approach to planning and decision-making;

- Incorporate multiple risks and their interdependencies – a good example is how geopolitical risks interact with economic risk both from a demand, cost, price and availability perspective;

- Use a variety of distributions to fit the underlying characteristics of the risks and consider non-linear and non-symmetrical outcomes, e.g. a number of the risks that will be considered are likely to be binomial; and

- A ‘probability times impact’ approach is unlikely to capture the true range of potential outcomes if the risk crystalises, as the impact will be best described as a range of outcomes.

However, it is not all about protecting against downside. There is clearly a place here for finding ways to get a competitive advantage from being better prepared than the competition. This could be from being able to respond more quickly and decisively as well as having identified possible market dislocations as a consequence of uncontrollables. For example, the steps we have outlined above should enable businesses to be more responsive and agile in responding to sudden, or permanent, changes to resource availability (and cost) even if these are driven by multiple and concurrent risks crystalising, for example, climate change leading to unexpected and severe weather events.

Uncontrollables raise significant governance and oversight issues due to their inherent complexity both from a downside as well as opportunity perspective. There are therefore additional oversight implications to focus on in order to ensure that the governance arrangements remain fit for a world of ‘dis-order’. Specifically, we recommend to:

- Review Board and committee mandates to ensure that they incorporate appropriate tests and questioning of how new uncontrollables are evidenced in risk frameworks and performance measures for incentives;

- Test policies for coping with permanent shifts – for example, implications for how we look at profitability, efficiency, elasticity of demand from inflation and other uncontrollables, and review whether any additional policies and processes are required to have a more comprehensive governance framework; and

- Test processes, like those related to business cases, for how they incorporate responses to uncontrollables – such as the impact of nearshoring, shifting investments from high to low inflation countries, testing vulnerability of operations from cost-cutting and dealing with sudden pension surpluses.

Conclusion

We recognise that both the management and Board agendas are getting squeezed and that it is challenging to find, and ringfence, sufficient time to have substantive discussions about uncontrollables and their potential implications. However, it is easier to have these discussions before rather than after the uncontrollables become more permanent. We also see that the organisations that take time to have these debates build a better understanding and awareness. They also find it easier to build ownership and understanding of the steps, and value, of preparing for adverse outcomes.

This article was first published in Governance, Issue 355 March 2024 (reprinted with permission), by Hans-Kristian Bryn and Carl Sjostrom.

Hans-Kristian Bryn

Share "Uncontrollables - coping with 'dis-order'" on

Latest Insights

UBS and Switzerland: Capital hikes are not the right tool for the job

15th October 2025 • Prasad Gollakota

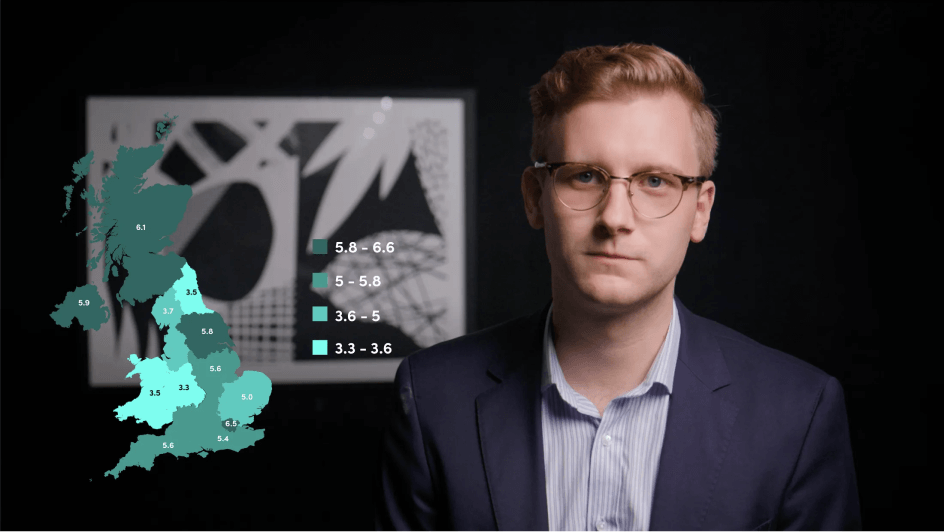

Trade deals & trade wars: The regional impact

23rd May 2025 • Adrian Pabst and Eliza da Silva Gomes

Unpacking the truth behind U.S. Treasury market volatility

17th April 2025 • Prasad Gollakota