Complexity: the good, the bad and the necessary

Hans-Kristian Bryn

35 years: Strategic risk management and governance

Understand how different types of complexity can impact your business and the potential risks and opportunities for each

Framing the complexity challenge

The complexity of business operations and the common assumption that strategy execution will take the organisation from one stable state to another, create significant problems for risk, performance and reward frameworks. The steady state assumption fails to take into account that most companies will experience disruption, chaos and uncontrollable events at the same time as operating day-to-day business. As a result, control is lost and it is often complexity that is blamed for any subsequent failure.

Complexity is a subject that is so diverse that there is not a single but a broad range of definitions across natural sciences, economics, mathematics and other academic disciplines. In this article, we will approach it from the perspective of complexity being a function of the number, stability and type of entities and their processes and relationships. Or in other words, complexity can be viewed as what and how we do things in how many versions, i.e. the organisational construct, and most importantly, how it all connects.

Most organisations treat complexity as being a negative and therefore the focus is on removing as much of it as possible by, for example, reducing product lines and simplifying the processes that underpin them. This presents the first governance issue, namely that stakeholders have different levels of understanding and therefore individual perceptions of the extent to which something is complex. The engineer understands the measurements of performance for his long-term incentive plan but often finds its rules for capital events difficult to understand, the Board understands the implications of capital events but often finds the incentive too complicated because of the performance measures, etc. This means that different parts of the company are likely to cope differently with complexity, depending on their respective perspective, expertise and experience.

The second governance issue is that most organisations do not incorporate complexity into planning and decision-making to ensure that they address it in a consistent manner, by identifying and classifying complexity and then defining appropriate actions and behaviours to manage value creation or remove value destruction. In the next sections we therefore propose a simple framework for making complexity a more integral part of planning and decision-making.

An alternative take on complexity

The challenge of complexity being perceived differently because of unique perspectives can to some extent be addressed with education and explaining the concerns of stakeholders to each other. But the definition set out above also allows us to address complexity from alternative angles and to recognise that complexity can be viewed as good, bad and necessary.

The organisational construct, what and how we do things and in how many versions, is probably what most see as driving complexity. This construct and the number of different types of both inputs and processes create an increasing level of difficulty of control. However, a company has to accept the complexity that is necessary to enter and remain in a chosen market. It also needs to work with complexity to gain sufficient advantage to allow a sustainable positive return, developing understanding and improving and innovating to make the offering attractive and resilient from uncontrollable events and competitors.

However, it is the stability and relationships of the organisational construct that make complexity non-linear and harder to work with. A company accepts this added dimension in order to, among other reasons, be more agile and able to adapt to a continuously changing environment. One of the challenges with such increased complexity is that the organisation will eventually struggle to cope and a typical reaction will often be to reduce all complexity regardless of its value contribution. Common examples can include exiting businesses, making employees redundant or reducing the number of products or services. All of these actions could be appropriate - as long as the complexity has been well analysed, assessed and prioritised in terms of being good, bad or necessary.

“Necessary complexity” is something organisations have to live with in order to remain in business. There may be legislative requirements and rules, as well as features that are fundamental to providing the product or the service. Necessary complexity is not something we can get rid of, per se, but we can consider whether aspects of it may also be either good or bad for the company.

“Bad complexity” is not limited to necessary complexity but is any complexity that destroys value for the company. In its clearest form it is the result of poor design, poor decisions or lack of critical review that has led to value erosion. Bad complexity can also be something that has evolved with the company over time but diverged from the business environment to a point where it has become a value destructive and unsustainable strategy, e.g. when a company has created barriers to its own success by being world leading in an obsolete technology without a presence in the growth markets of the future.

“Good complexity” instead creates, maintains or protects value for the company. This may be by creating a better offering, protecting critical resources or by building barriers to competition. The better offering may come from allocating resources into areas like innovation, variety and quality where the complexity is value adding or protecting the future survival of the company. Barriers to competition can overlap with “necessary complexity” and an example would be where large incumbent companies work with regulators to impose rules on certain types of products or solutions that then makes it prohibitively expensive for smaller actors to enter and thrive in the sector.

Recognising that no single state is likely to be “steady” and that, through the journey from past to present to future, different types of complexity have different potential impact on a company, the next step is to bring into the review processes an analysis of how to minimise bad whilst maximising good complexity, including how to shift bad and necessary towards good complexity:

- Minimise bad complexity: as bad complexity destroys value it should be the focus of ongoing review to reduce and eventually eliminate it. Typical indicators are where complexity creates functionality or features the buyer doesn’t value or is willing to pay for.

- Shift bad complexity to good: bad complexity can sometimes be turned into “good” complexity, where it is either appreciated by the markets or in other ways creates a barrier to competition that makes it value adding. For example, professions and guilds have historically kept competition at bay by adding complexity to products, services and processes that in turn reduce competition and allow higher prices to be charged.

- Improve necessary complexity: necessary complexity should not just be accepted but should also be evaluated for how it can be improved. Necessary complexity is a key contributor to barriers to competition and if what is necessary to produce the product or service can be shifted to the benefit of the company, for example through disruptive innovation, then this can create a significant value boost. Similarly, working to make regulatory, legal and governance requirements a positive for the company can turn a complex negative at least neutral, for example by turning environmental restrictions into a positive selling point for products and services

- Improve good complexity: good complexity adds value, which will provide longer-term benefits to the extent that barriers to competition are created and maintained. These barriers ensure that competitors and new entrants form as small a threat as possible - but it also involves risks. As per evolutionary theory, barriers to competition help the survival of the fittest but there is also a risk of evolving into being obsolete. Hence it is critical that good complexity is managed so that it remains relevant for both present and future requirements.

A risk perspective on complexity

Our classification highlights how increases in bad complexity can be an unintended consequence of past and current decisions. In addition, we have identified that businesses get disrupted and experience uncontrollable events, factors that can add further bad complexity, disturbing the transition to a future state. It is therefore key that complexity and management actions in response to these risks are considered in an explicit and integrated manner.

“Complexity risk" has previously been defined as a risk which crystallises when the behaviour of an organisation (or a part thereof) becomes difficult to understand, model, or control, and therefore making it more challenging to anticipate and mitigate potential adverse consequences. The variables that drive this difficulty are in, particular, the numbers and stability of relationships between entities and processes.

In a risk management context, complexity risk is hardly ever addressed explicitly – nor as an opportunity. As a consequence, organisations don’t assess adequately whether the complexity in questions is good, bad or necessary. Equally, the level of complexity risk is to a large extent a function of past decisions (e.g. organic or inorganic growth), sometimes with unintended consequences as the decisions were not tested with regards to increases or decreases in different types of complexity. From a value creation perspective, it is therefore important to get clarity on complexity in terms of:

- What are the legacy causes or drivers of complexity?

- What is the current level of and type of complexity?

- What is a desired future state – how much complexity and what type?

In many ways, there are parallels between concentration risk and complexity risk in that they are often hidden rather than addressed explicitly. One can think of examples such as high dependency on specific suppliers or supplier regions which have been pursued on a cost and efficiency agenda without consideration of the complexity this might give rise to in the event of a supplier failure or supply-chain disruption in the region.

Putting the spotlight on complexity also helps to avoid the pitfalls of increasing bad complexity as an unintended consequence of the pursuit of simplification or cost reduction. However, enhanced analysis of complexity is not sufficient to achieve the organisations’ intentions. The reward systems also need to be designed to encourage the right actions and behaviours to deliver the desired complexity outcomes.

Complexity and remuneration

Remuneration, in particular the design of executive pay arrangements, is an area that is often itself accused of complexity. Though there is plenty of necessary complexity created by regulatory and legal requirements, there are also many examples of bad complexity from over-design and under-appreciation of the benefits of keeping reward mechanisms simple. However, remuneration also fulfils a key role in making good complexity work and, importantly, in helping organisations shift from one type of complexity to a more preferable one.

First, the primary strength of incentives is to provide a way of signalling what is important with regard to the actions and behaviours that should drive success. This matters as complexity tends to, on the one hand, make people err towards their “cognitive bias” and, on the other hand, create rigidity in collective actions. In other words, executives and employees will generally make judgements biased by their personal circumstances whilst worried that pursuing positive change could be punished unless they see meaningful evidence, guidance and encouragement to the contrary.

Incentives are a key mechanism to provide such reassurance by rewarding actions and behaviours that are more aligned with the strategy and intentions that owners want to pursue. Incentives can even indicate governance failing to deal with complexity, such as when strategies are not reflected in incentives’ performance conditions, showing that the Board has rejected good complexity (alignment of required actions and behaviours with reward) to avoid having to educate stakeholders, thereby inadvertently increasing bad complexity by weakening the relationship between key entities (e.g. management and strategy) and their stability (e.g. understanding of what is expected).

Second, incentives are a prompt to evaluate both how the organisation has evolved to its current structure and what the future may bring. For many companies, complexity inadvertently encourages a focus on the past. Looking to continue positive change that has previously been perceived as effective is often the path of least resistance, for example by setting the baseline of performance as the prior year’s outcome. Similarly, complexity tends to drive towards generalisations of performance expectations, such as single profitability measures and fixed ranges of outcomes regardless of business or market characteristics.

Accepting and evaluating the complexity of non-linear relationships between inputs, events and outputs can help the organisation to recognise its exposure to market factors and to set targets and aspirations based on more detailed analyses of risks and opportunities. It also highlights that what may have been good complexity in the past and present can create barriers to success in the future, which will be difficult to break down if reward mechanisms protect them. For example, an incentive that promotes the continued focus on selling a mature technology will struggle to shift to a strategy of selling a new and growing one as long as it remains easier to maximise the sales incentive with legacy product revenues.

Finally, increased complexity from less stability and more points of contact with stakeholders and uncontrollables means that the links between input and outcomes become less linear and therefore more difficult to predict. This is a challenge for many companies that seek linear relationships between performance and reward, in particular over longer time periods. This is addressed by recognising non-linearity, the structures of incentives and how the company balances elements of reward with the context of the business. Recognising non-linear complexity through balancing fixed and variable, financial and non-financial, and short- and long-term remuneration allows reward solutions that encourage the right actions and behaviours, generating a suite of possible performance and reward outcomes that is value adding for both owners and recipients of reward.

Conclusions

This article challenges the conventional wisdom that complexity is always a negative and provides an approach to assessing it in terms of its impact on value. We have also set out how working with bad or necessary complexity can be turned into a strategic advantage when incorporated into planning and decision-making, not least through the way risk, performance and reward are considered.

In summary, risk, performance and reward considerations in a business case process should explicitly address complexity and consider the extent to which it is creating or destroying value. There are many practical steps that organisations can take to identify both the level and type of complexity in the current business model, as well as steps to reduce unwanted or bad complexity, whilst identifying ways in which competitive advantage and customer stickiness can even be improved by taking on good complexity. Due consideration of complexity will hence help ensure that key choices, for example strategy, portfolio, M&A and capex decisions, maximise the value impact.

This article first appeared in Governance Publishing and is co-authored by Carl Sjostrom and Hans-Kristian Bryn.

Hans-Kristian Bryn

Share "Complexity: the good, the bad and the necessary" on

Latest Insights

UBS and Switzerland: Capital hikes are not the right tool for the job

15th October 2025 • Prasad Gollakota

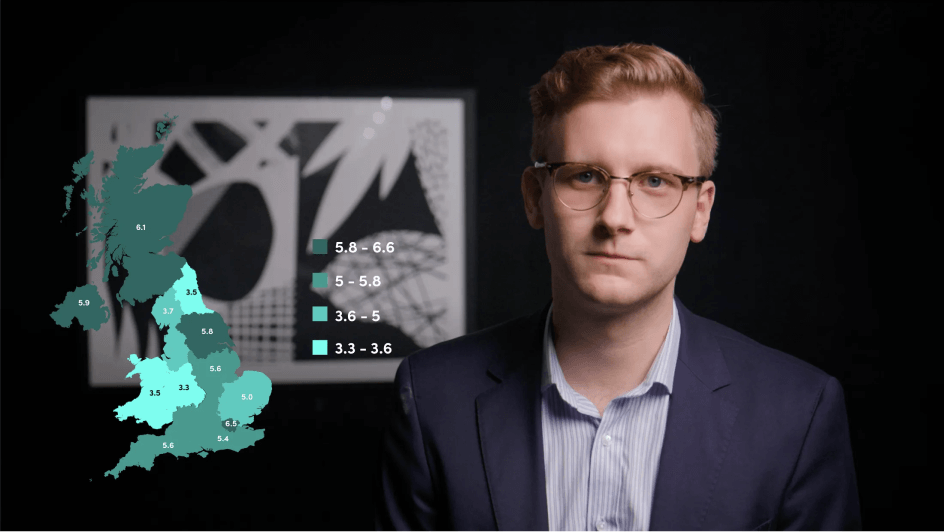

Trade deals & trade wars: The regional impact

23rd May 2025 • Adrian Pabst and Eliza da Silva Gomes

Unpacking the truth behind U.S. Treasury market volatility

17th April 2025 • Prasad Gollakota