SVB: A catastrophic failure demystified

Paul Newson

20 years: Market Risk

The basic facts surrounding the collapse last week of Silicon Valley Bank seem clear. During 2021, the bank’s deposits increased by $89bn and the majority of this money was invested not in customer loans but in fixed-rate bonds, mainly mortgage-backed securities.

Introduction

At the end of 2021, these bonds accounted for $127bn of the bank’s total of total assets of $211bn. The rise in interest rates during 2022 obviously reduced the market value of these bonds, meaning that when the SVB began to suffer a material outflow of deposits, repayment would only have been possible by realising what might otherwise have been passed off as only a temporary and “theoretical” loss – i.e. something that would have reversed over time had the bank been able to hold the bonds (and, of course the deposits) until their final maturity.

Failure of risk management and ALM practices

Without a shadow of doubt, SVB’s collapse constitutes a catastrophic failure of ALM risk management, so it is pertinent to consider how on earth it could have happened and why such a blatant balance sheet risk was tolerated not only by the risk management function but also by the whole of the bank’s senior management team. Did they not understand the risks or did they just decide to ignore them in the belief that somehow they would not crystallise?

To be clear, investing assets at a fixed rate for a given period of time – in this case over 10 years – exposes you to rates rising unless fixed-rate funding of equivalent maturity can be raised. Or at least manufactured by interest-rate swaps – i.e. swapping fixed cashflows for floating. This is pretty fundamental.

So what were people thinking? Until investigations have been completed and published, no one can really know. One possibility, however, is that they naively believed – or were persuaded to believe – that because the bulk of the deposits were non-interest-bearing ($126bn out of $189bn at end-2021), they already constituted the necessary fixed and permanent funding of the $127bn of fixed-rate bonds. In other words, the argument may have been that any rate rise would not matter much from an income perspective because they paid nothing on the deposits anyway, while a potential fall in market value of assets was equally irrelevant as there was no intention to sell them. They may even have thought that investing fixed was a protection from rates falling.

Structural hedging and misguided assumptions

Now, so called “structural” or “margin compression” hedging of non-dated deposits (NMDs) has been fairly common practice among larger retail and commercial banks for years. The big difference, however, is it is only ever appropriate if you can be absolutely sure that the deposits will remain with you for at least the term of the fixed-rate assets and that they will not need to be re-priced if rates rise. To ensure these conditions are met, normal ALM practice, requires the following:

- A clear demonstration, based on past history, that the deposit portfolio has to-date displayed a very high degree of stability, particularly in response to previous rate changes and even then to apply a very prudent haircut in case things should change. Here, we appear to have had a near 100% investment of the portfolio, the majority of which had only been acquired very recently.

- A careful examination of the type of deposit so as to check for any undue concentrations. A portfolio comprising a large number of small deposits is less likely – in aggregate – to be rate sensitive than a portfolio comprising a smaller number of large deposits. Simply put, someone whose average balance is $2,000 only gains $40 a year by moving to an account paying 2% whereas a depositor with $2,000,000 strands to gain $40,000. The latter is probably more likely to move their money if rates rise and, by all accounts, SVBs deposits mainly comprised a small number of very large deposits.

- The picking of an appropriate investment term. Typical terms for the banking sector are around five years. Anything much longer means locking into a rate which could, in years to come, be significantly lower than whatever the new norm might be. It also implicitly requires a belief that even a prudent projection of deposit stability will remain valid for a considerably longer period than any bank can reasonably plan. Ten years looks rather long.

- The use of a rolling portfolio of assets (usually swaps) rather than cash-based instruments. In this way, a constant maturity can be maintained and the hedge can be more readily adjusted should deposit retention assumptions prove incorrect.

Whether any of these points were ever considered is unknown at this stage, but if the risk function did allow itself to be persuaded that this was an appropriate structural hedge – and this is just a hypothesis – then, far from it being an excuse, it arguably shows it in an even poorer light. Being either unaware of a risk or being powerless to challenge it are serious enough failings but endorsing, implicitly or otherwise, a simplistic risk management technique without undertaking even the most basic checks is almost worse. As Alexander Pope pointed out over 300 years ago: “a little knowledge is a dangerous thing”.

SVB EVE measurement and confusion

Another point worthy of note is that SVB in its 2021 annual report did publish the results of its internal Economic Value of Equity (EVE) measurements and, indicated, in the commentary, that it had in March 2021 entered into some swaps to reduce it – presumably paying fixed. This at least shows that there was some awareness both of the risk itself and an acknowledgement that it was getting too big. This, however, raises more questions than it answers:

- There are no details of exactly how the numbers were computed, particularly whether any behavioural maturity was assigned to the non-interest-bearing deposits – if so, this might possibly have reduced the number.

- Regardless of how it was calculated, a $5.7bn exposure to an up to 200bp rise relative to capital of $16.6bn shock is still huge – a ratio of 34%. The Basel Standards for IRRBB, or Interest-Rate Risk in the Banking Book, state that any bank whose EVE sensitivity to +/- 200bp parallel shocks is greater than 15% of Tier 1 capital is an “outlier” and should be reported to its regulator immediately. It is noteworthy, that the US has not adopted this requirement.

- If the $5.7bn figure is after the hedge, what was it before? One can only assume that it was much larger – hence the corrective hedge – but by the same token, it follows that $5.7bn was somehow regarded as acceptable. This suggests that, although the bank’s risk function performed and indeed published the calculation, no one really believed that, in reality, the risk would ever actually crystallise.

Interestingly, but probably not surprisingly, SVB did not elect to publish its EVE sensitivities in the 2022 annual report and accounts – it merely presented some 12-month NII sensitivities.

All this, however, is hypothesis based on the few facts and number that are available. The wider point is that EVE risk in banking books should be far, far lower. Furthermore, whatever appetite might be set, it should be solely for the purposes of accommodating peak customer flow and associated operational leads and lags – it should not be there not to facilitate open risk taking. The job of the risk function in a banking book is not just to check compliance with any formal limit but also to ensure any risk positions – even within that limit – have been incurred for good reason and will be closed shortly. To re-iterate, this position was inherently speculative – in order to achieve a slightly higher coupon by investing in fixed rather than floating-rate bonds they were essentially betting that over $100bn of non- interest bearing deposits could be retained regardless of any external events (e.g. a rise in rates), or, alternatively that rates would not rise.

So much then for what may or may not have happened at the outset. What then transpired was, of course, that the non-interest-bearing deposits started to be withdrawn. The fixed asset position consequently became increasingly funded by variable as opposed to no--interest-bearing deposits thus crystallising the inherent risk. It is relevant, therefore, to consider what the drivers may have been to this outflow of funds.

First, the bank obviously suffered a run when its depositors finally woke up to the fact –or were told by their advisors – that there was something seriously wrong. This, however, is not particularly unusual. Banks can only operate and survive if they continue to enjoy the confidence of their depositors but this can evaporate in hours. The driver of deposit withdrawal in recent weeks was simply fear and this was entirely understandable as, at the time, the maximum protection any depositor could have hoped for was $250,000; most deposits were clearly much larger.

Perhaps more instructive, in respect of lessons to learn is to think about what might have been the drivers of the more gradual loss of non-interest-bearing deposits that occurred beforehand when, presumably, most depositors still imagined that the bank was solvent.

Drivers of deposit outflows and sector concentration risk

Comparing SVB’s end-2021 and end-2022 balance sheets, it can be seen that total customer deposits fell from $189bn to $173bn. Even more significantly, the mix altered: non-interest-bearing deposits fell from $125bn to just $81bn while interest-bearing deposits increased from $63bn to $92bn. What, then, prompted this outflow during 2022 of over a third of SVB’s non-interest-bearing deposits?

One obvious driver is that depositors were simply proving to be rather more rate sensitive than had previously been imagined and many were probably moving their funds into interest-bearing accounts either at SVB or at other banks. As discussed above, large deposits whether from high net worth individuals or from companies with large temporary cash surpluses are more likely to be rate sensitive, so assuming that they will all be retained in the event of rate rises is foolish and highly dangerous.

Another possible driver was what we might term sector concentration risk. From the little we know, many of the deposits came from the “tech sector” - comprising both operational deposits from the tech companies themselves and, by all accounts, individual deposits from their owners and other stakeholders in that industry. Some of the decrease in total balances may, therefore, have been the result not of conscious decisions by deposit holders to move their money elsewhere to get a better rate, but simply reflective of the fact that, collectively, these companies and individuals had rather less ready cash by the end of 2022 than they did at the beginning.

Again, the lesson here is to understand the deposit base. For a large retail commercial bank with a well-diversified depositor base, a decrease in deposits from one sector is likely to be largely offset by an increase in other deposits – the money has to go somewhere – but a bank focused on serving just one sector of the economy is going to find its fortunes rise and fall in line with that sector. It cannot, therefore, make the same assumptions about aggregate deposit stability as a more diversified bank can. This is probably a factor that, to-date, has received relatively less attention in the management of IRRBB. While practitioners and regulators rightly focus on the risk of deposits moving or re-pricing in direct response to an interest-rate change, it is also important to consider other potential drivers of deposit loss. Following the collapse of SVB, it would seem that sector concentration risk on the liability side is probably something that needs to move up the IRRBB agenda.

Lessons learned

What lessons then can be learned?

- Don’t run large open risks in the banking book to boost short-term income.

- Ensure that there is proper independent, confident and competent risk management function.

- Don’t manage within risk appetites – formal or informal - unless you believe the numbers and have the capacity to absorb any potential losses that they imply.

- Don’t fondly imagine that large unremunerated cash deposits will necessarily remain with you in perpetuity.

- If you do elect to hedge part of your NMD portfolio, don’t invest or hedge 100% of it. Instead, undertake proper analysis of these deposits paying particular regard to how long they have been with you, the stability they have previously displayed and any sector, size or other concentrations that may exist.

Paul Newson

Share "SVB: A catastrophic failure demystified" on

Latest Insights

UBS and Switzerland: Capital hikes are not the right tool for the job

15th October 2025 • Prasad Gollakota

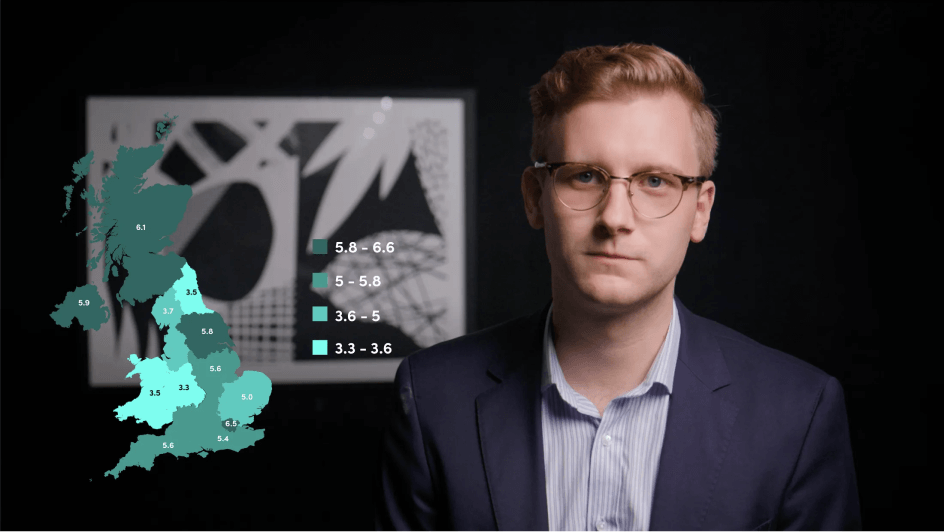

Trade deals & trade wars: The regional impact

23rd May 2025 • Adrian Pabst and Eliza da Silva Gomes

Unpacking the truth behind U.S. Treasury market volatility

17th April 2025 • Prasad Gollakota