What does a Trump victory mean for the global economy?

Ahmet Kaya

Principal Economist at NIESR

Understanding the potential effect of proposed changes in tariff policy

On 5 November, Donald Trump won the US presidential election after what was arguably one of the most consequential races in recent decades. Although he will not assume the office until January, Trump has already pledged to end the war in Ukraine, repeal the Affordable Care Act (also known as Obamacare), cut taxes, slash government spending, and intensify deportations of undocumented migrants. However, his most contentious promise was a substantial increase in import tariffs.

During the election campaign, Trump repeatedly promised to impose a 60 per cent import tariff on all products from China and 10 to 20 per cent tariffs on products from other countries. While the details regarding how and when this policy will be implemented – and which goods and services will be affected – are not yet clear, such measures are expected to deliver another shock to the global economy, increasing trade fragmentation.

How could tariffs affect the US economy?

Higher import tariffs in the United States increase import prices and reduce imports. Proponents of tariffs argue this may benefit gross domestic product (GDP) by improving the trade balance and potentially shifting demand to domestic production. However, things become more complicated when we consider the second-round impacts of tariffs on the economy through exchange rates, inflation and interest rates.

First, higher tariffs lead to the appreciation of the US dollar, which makes US exporters less competitive in international markets. Coupled with potential retaliation from other countries, which will make US products even costlier abroad, US exports are likely to be affected negatively, potentially erasing any improvements in the trade balance due to lower imports.

Second, higher import prices pass through to higher inflation. Consumers face either higher prices for imported goods and services, or switch to more expensive domestic alternatives. In either case, they will have less money to spend on other goods and services, meaning that real disposable income (and thus consumption) would drop.

Third, not all imports are final products that US consumers purchase. This is especially true for the import of goods, which consist of raw materials and intermediate goods used in the production of final products. Trump’s proposed “blanket tariffs” on all imports are therefore likely to hurt supply chains in domestic industries, reducing investment.

Finally, higher inflation due to tariffs would pressure the Federal Reserve (Fed) to increase interest rates, further hurting investment in the domestic economy. Overall, US GDP is likely to be negatively affected by tariffs.

How could other countries be affected?

Countries subject to trade tariffs would experience an increase in effective export prices, subsequently leading to a decline in export volumes. This would worsen their trade balances and negatively impact output. And the effects are likely to be worse once we consider the secondary impacts.

While inflationary pressures may ease slightly as goods previously intended for export remain in the domestic market, currency depreciation due to tariffs can drive inflation higher. This inflationary effect also forces their central banks to tighten monetary policy, further impacting investment and consumption, ultimately leading to a decline in real GDP.

What exactly could the impacts be for the United States and China?

A special report from the National Institute of Economic and Social Research (NIESR) analyses the global macroeconomic effects of a tariff shock. Figure 1 illustrates the impact on real GDP growth rates in the United States and China, compared to an alternative scenario of no additional tariffs. In the United States, tariffs reduce the GDP growth rate by about 1.3 percentage points in the first year, with this effect gradually tapering over three years.

The negative impact on GDP growth would intensify if tariff-exposed countries retaliate with equivalent increases in tariffs on US goods. In this scenario, US GDP growth would be approximately 1.7 and 1.5 percentage points lower in the first and second years, respectively, following tariff implementation. Meanwhile, Chinese economic growth would be about 1 percentage point lower on average over the two years after the tariff increase.

Higher tariffs also drive inflation up in the United States by between 3.5 and 5 percentage points, depending on whether their trading partners respond with their own tariffs against the United States. As noted, this inflationary pressure would likely prompt the Federal Reserve to raise interest rates by around 3.5 percentage points, further hitting investment and amplifying the initial negative impact on US GDP.

On the other hand, the analysis projects that China’s inflation rate would drop by approximately 1.3 percentage points if they do not retaliate. This decrease would result from an increased domestic supply of goods and services as exports decline, combined with a negative output gap created by reduced export demand, both of which exert downward pressure on prices.

Impact on the global economy

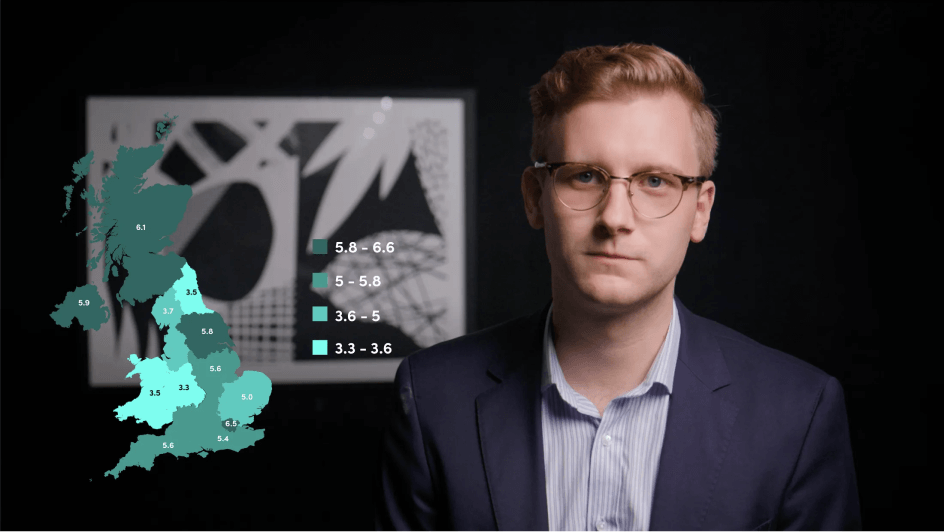

Figure 2 shows the impact of US tariffs on real GDP in different countries, highlighting those most affected due to their trade ties with the United States and their levels of trade openness. Mexico, with around 80 per cent of its exports going to the United States, is the hardest hit, experiencing a reduction in GDP of approximately 5 per cent over five years, compared to the alternative scenario of no additional tariffs. Canada, similarly, exposed with around 75 per cent of exports directed to the United States, sees its real GDP drop by around 3.5 per cent in the same period. Other countries that are most affected by US tariffs include small open economies such as Switzerland, Hungary and Poland, which are sensitive to shifts in global trade dynamics.

Figure 3 illustrates the long-term global GDP impact of US tariffs, showing a persistent negative effect over 15 years. Initially, global GDP would be around 0.7 per cent lower than without the additional tariffs, with the impact gradually intensifying over the next few years. By the fifth year, the negative effect on global GDP reaches around 2.5 per cent, stabilising at this level over the long term. Notably, the chart shows that whether or not tariff-exposed countries retaliate does not significantly alter the overall impact on global GDP; both scenarios result in similar long-term declines.

In sum, Trump's proposed tariffs are likely to create ripple effects across both the US and global economies, affecting GDP, inflation and trade flows. While proponents argue that tariffs could boost domestic production, the second-round effects imply a number of downsides, such as higher consumer prices, disrupted supply chains, and retaliatory measures that could harm US exports. For other countries, especially those with close trade ties to the United States, the impact could be severe. Ultimately, these tariffs may lead to a more fragmented global economy, with slower growth and long-lasting negative consequences for global GDP over the long term.

Ahmet Kaya

Share "What does a Trump victory mean for the global economy?" on

Latest Insights

UBS and Switzerland: Capital hikes are not the right tool for the job

15th October 2025 • Prasad Gollakota

Trade deals & trade wars: The regional impact

23rd May 2025 • Adrian Pabst and Eliza da Silva Gomes

Unpacking the truth behind U.S. Treasury market volatility

17th April 2025 • Prasad Gollakota