Did inflation and unemployment defy the Phillips curve in 2024?

Prasad Gollakota

20 years: Capital markets & banking

The necessity of re-evaluating concepts like the Phillips curve.

The Phillips curve, a foundational concept in macroeconomics, posits an inverse relationship between unemployment and inflation: as unemployment decreases, inflation tends to increase, and vice versa.

This relationship has historically guided policymakers in balancing economic growth and price stability. However, recent economic developments, particularly in 2024, have challenged the traditional dynamics of the Phillips curve, prompting a reevaluation of its applicability in contemporary economic forecasting.

Defining ‘low’ inflation and ‘high’ unemployment

In the context of economic analysis, low inflation and high unemployment are generally considered within ranges, though they may vary depending on the economic environment and region.

Low inflation is a sustained period where price increases are minimal, typically close to or below a central bank's target rate (usually around 2% annually for many developed economies). In the Eurozone and U.S. inflation rates below 1% are often considered low, as they indicate subdued price growth that may signal weak demand.

Unemployment is considered ‘high’ when it is significantly above what is referred to as the "natural rate of unemployment", which in developed economics is expected to be 3-5%.

Understanding the Phillips curve

Introduced by economist A.W. Phillips in 1958, the Phillips curve illustrates the trade-off between unemployment and inflation. The underlying theory suggests that low unemployment leads to higher demand for goods and services, which in turn leads to rising wages, which can drive up prices, resulting in inflation. Conversely, high unemployment is associated with lower wages and therefore lower demand, exerting downward pressure on prices and leading to lower inflation (or even deflation).

For decades policymakers have used the Phillips curve to inform decisions on interest rates and other monetary policies. For instance, central banks might raise interest rates to cool down an overheating economy (with low unemployment and rising inflation), or lower rates to stimulate economic activity during periods of high unemployment and low inflation.

The Phillips curve in 2024

Deviations from the curve often coincide with atypical economic conditions, such as stagflation in the 1970s (high inflation and high unemployment), the low inflation of the 2010s despite declining unemployment, or the disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

In 2024, the U.S. economy exhibited patterns that appeared to deviate from the traditional Phillips curve relationship. Despite a relatively low unemployment rate, inflation remained subdued, challenging the expected inverse correlation.

- Unemployment Trends: As of October 2024, the U.S. unemployment rate stood at 4.1%, reflecting a slight increase from the previous year but remaining historically low.

- Inflation Trends: During the same period, the Consumer Price Index (CPI) in the U.S. indicated an annual inflation rate of 2.6%, aligning closely with the Federal Reserve's target and showing a decline from the higher rates observed in preceding years.

This simultaneous occurrence of low unemployment and moderate inflation suggests a weakening of the traditional Phillips curve relationship.

Factors contributing to the Phillips curve breakdown

Several factors have contributed to the apparent decoupling of unemployment and inflation in 2024:

- Global supply chain dynamics: The COVID-19 pandemic and geopolitical tensions have disrupted global supply chains, leading to supply-side constraints that affect prices independently of domestic labour market conditions.

- Technological advancements: Automation and digitisation have increased productivity, allowing firms to meet rising demand without proportionally increasing their need for labour, thereby mitigating wage pressures that typically lead to inflation.

- Labour market changes: The composition and behaviour of the labour force have undergone significant shifts in recent years. Demographic changes, such as an ageing population in many countries, mean fewer people are available to work, which can lower overall participation rates. Additionally, changing work preferences, like the rise of remote work, increased focus on work-life balance, and the growth of gig and freelance economies, have influenced how and when people choose to enter the workforce. These factors affect employment levels but do not necessarily create the wage pressures that traditionally lead to inflation, as the labour market adjusts in ways that are not always tied to higher wages or greater consumer demand.

- Globalisation: Access to international labour markets and goods has intensified competition, exerting downward pressure on wages and prices domestically, which can suppress inflation even amid low unemployment.

- Anchored inflation expectations: Central banks play a crucial role in shaping how the public perceives future inflation. When a central bank has a strong track record of keeping inflation under control, businesses and households trust that inflation will remain stable over time. This trust is referred to as "anchored inflation expectations."

As a result, people are less likely to react dramatically to temporary changes in the economy, such as fluctuations in unemployment. For example, if unemployment decreases, businesses might typically raise wages, and higher wages could lead to higher prices (inflation). However, if people believe inflation will remain steady because of the central bank's credibility, they may not adjust their behaviour in ways that would trigger inflation, such as demanding large wage increases or preemptively raising prices.

This phenomenon helps "anchor" inflation, making it less sensitive to short-term economic changes and weakening the traditional relationship predicted by the Phillips curve.

Prasad Gollakota

Share "Did inflation and unemployment defy the Phillips curve in 2024?" on

Latest Insights

UBS and Switzerland: Capital hikes are not the right tool for the job

15th October 2025 • Prasad Gollakota

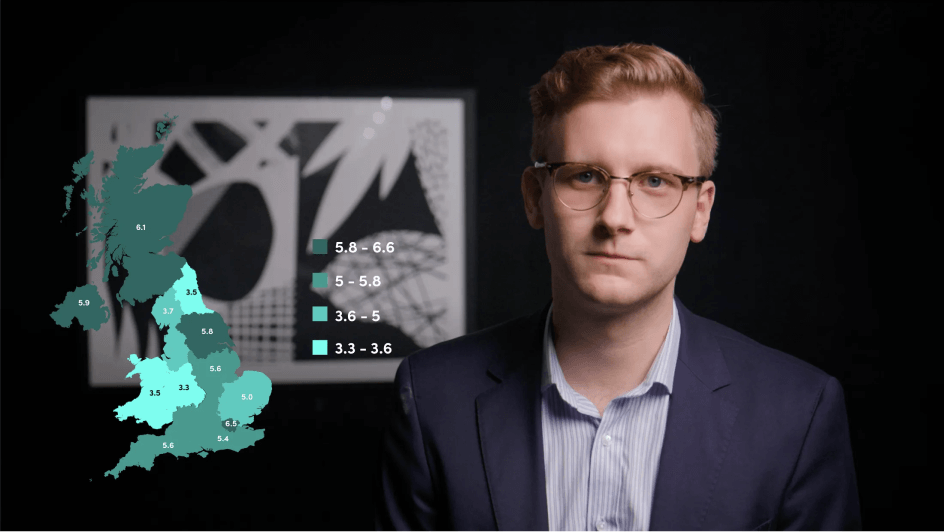

Trade deals & trade wars: The regional impact

23rd May 2025 • Adrian Pabst and Eliza da Silva Gomes

Unpacking the truth behind U.S. Treasury market volatility

17th April 2025 • Prasad Gollakota